where have all the flowers gone?

06 December, 2025 - 04 January, 2026

Location

Arnold and Sheila Aronson Galleries

66 5th Ave.

New York, New York 10011

Where Have All the Flowers Gone? marks the first public presentation including The New School’s art collection in over six years in a rare exhibition that places works by contemporary artists who have served in the armed forces in direct dialogue with the postwar and contemporary canon. At a university shaped by a century of progressive thought and critical theory, this convergence of veteran and civilian voices presents a powerful and unlikely exchange—one that foregrounds perspectives rarely (if ever) made visible in contemporary art discourse.

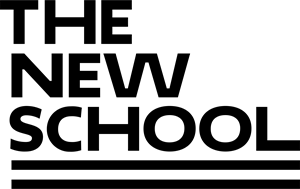

Taking its title from Pete Seeger’s 1955 song about the cyclicality and futility of war, and building upon Sister Mary Corita Kent’s 1969 serigraph Manflowers (in which Seeger’s refrain appears), the exhibition brings together artists who return to that question anew. Where Have All the Flowers Gone? offers a humanizing take on service that resists both heroic abstraction and easy condemnation. Instead, the exhibition reveals the grey areas where loyalty and doubt, service and conscience, coexist.

From postwar Europe to contemporary America, this selection of work unearths shared ground beneath those who have worn the uniform and those who have observed from without. In this collaboration, uncomplicated boundaries between consent and dissent are broken, making space for nuance and a shared need for purpose, belonging, protection and survival.

Sister Mary Corita Kent Manflowers, 1969

Serigraph

11.5 x 22.5 inches

Purchase

The New School Art Collection

Installation view, Where Have All The Flowers Gone?, Arnold and Sheila Aronson Galleries, New York, NY

“The exhibition acknowledges recurrent motifs in artistic portrayals of military bodies, while also considering how and why such recent portrayals differ from historical ones.”

-Louis Bury, exhibition essay: “Where have all the Flowers Gone?”

Julianna Dail, Modern Retreat, 2008-09 (detail)

Nylon rope, acrylic paint, and resin

8 x 64 x 36 inches

“My woven pants pieces were made during another time that some (many?) felt was in an upheaval. While making modern retreat, I was thinking about the mythological story of the Greeks leaving the Trojan horse at the gates of Troy. As questions rose in 2008 about how to end the wars the U.S. was involved in, this installation stemmed from my questioning the definition of modern retreat. What do people retreat from, what is the effect, and how often are their true motives concealed?”

—Julianna Dail

Enrique Chagoya, The Ghost of Liberty, 2004

Color lithograph, chine colle on paper

11.5 x 85 inches 29.2 x 215.9 cm

Edition 30,AP1/6

Purchase

The New School Art Collection

“Made with donated U.S. military uniforms added during the firing, each vessel in Residue is inscribed with smoke as the uniform material burns. The carbon from the fabric adheres to the raw clay while the glaze is reduced and creates a range of surfaces that shift from gunmetal to chrome.

This single formation of fifty vessels is part of an ongoing body of work that will expand to 1,000 for the next exhibition and ultimately reach 3,500; one for each thousand U.S. veterans estimated to have been exposed to toxic burn pits during their deployments. Each vessel is a physical index of that exposure, connecting material and memory and the residue of service.”

Ian Manseau, Residue (Formation of 50 Vessels), 2025

28 x 24 x 5 inches

Ceramic, glaze, donated military uniforms

— Ian ManseauJoshua Prince

Snowflakes

2023

Shredded copy paper, multiplate lithograph, and cardboard

Installation – dimensions vary (lithograph 15 x 22 in.)

Juan Genovés

Escalada

1967

Oil on canvas

79 x 59 1/4 in.; 200.7 x 150.5 cm

Gift of Barbara Levinson

The New School Art Collection

Enrique Chagoya

The Ghost of Liberty

2004

Color lithograph, chine colle on paper

11.5 x 85 in.; 29.2 x 215.9 cm

Edition 30, AP1/6

Purchase

The New School Art Collection

Nicole Goodwin

Ain't I a Woman (?/!): Kingston Legacy IV

2021

Photographic (inkjet) triptych of performance

21 x 8 in.

Kevin Sparkowich

Nuclear Family

2025

Oil on linen

38 x 56 in.

Sister Mary Corita Kent

Manflowers

1969

Serigraph

11.5 x 22.5 in.

29.2 x 57.2 cm

Purchase

The New School Art Collection

Alejandro Emilio Aguirre

Undisclosed: Home is what you make it.

2025

Inkjet print

24 x 18 in.

Luek Collins

Portrait of My Mother (Nude, Wearing My Father's Dog Tags) and Self Portrait (Nude, in Front of the Gun Wall in My Father's Doomsday Bunker), from God is a Talented Liar

2025

Polaroid

10 × 10 in. framed

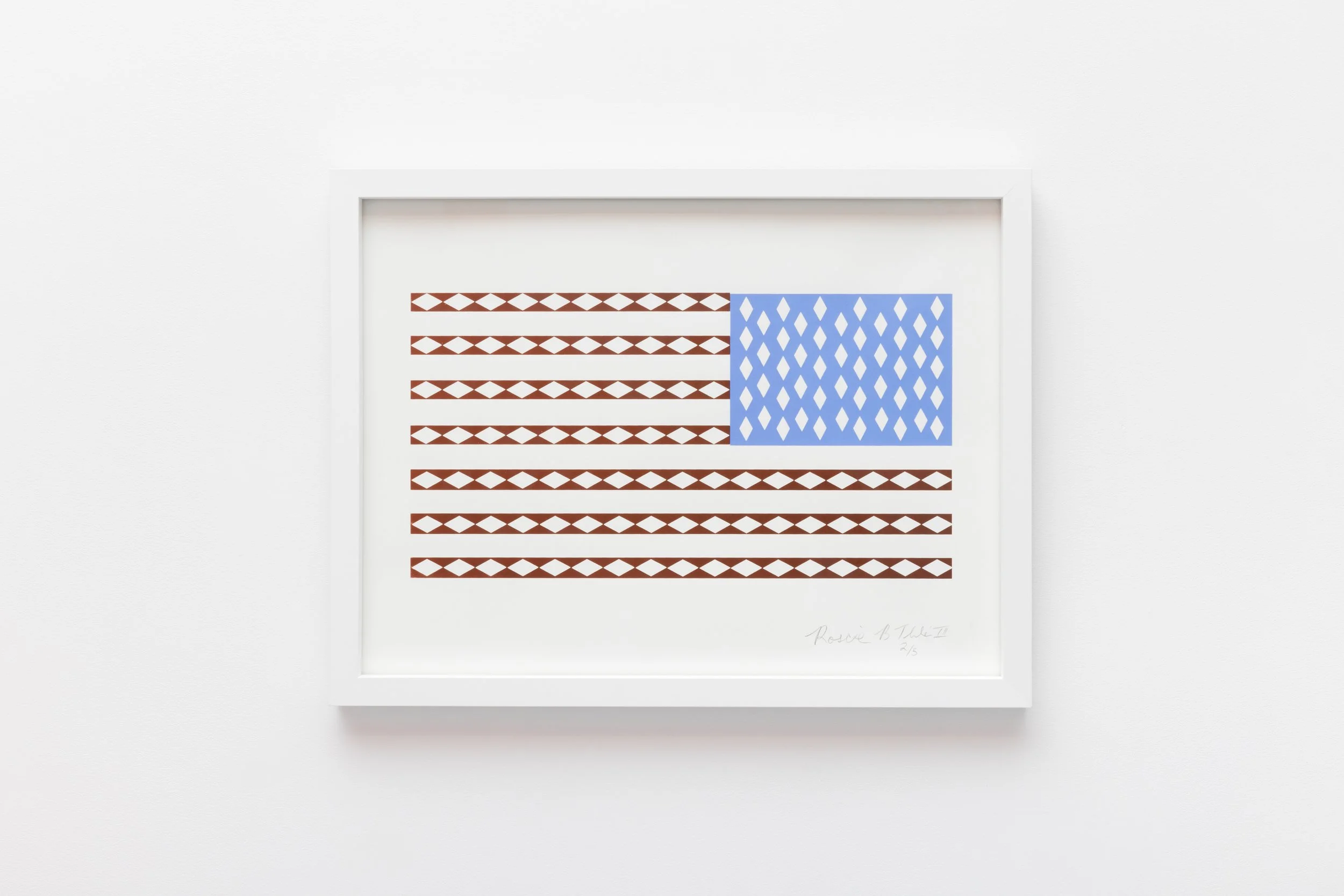

Roscoe B. Thicke III

Liberty City

2024

Silkscreen on 250 gsm Coventry Rag

18 x 24 in.

Signed Edition

Courtesy of OSMOS, New York

Katrina Buckles

Washington Monument

2025

Inkjet print

8 x 10 in.

Ian Manseau

Formation (Failed)

2025

Charcoal from burned military uniforms on handmade Combat Paper

11 × 14 in.

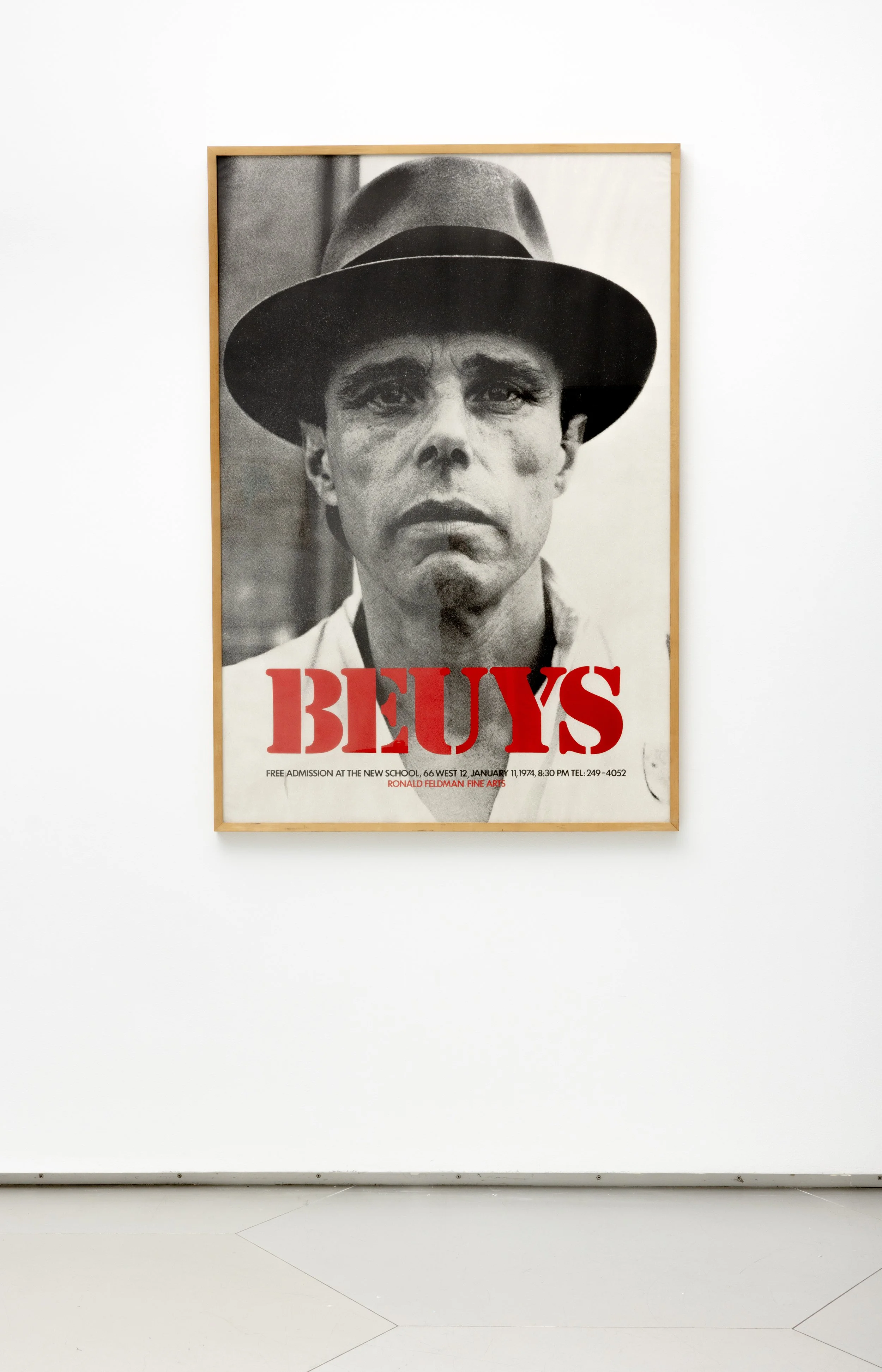

Joseph Beuys

Joseph Beuys at the New School (poster)

1974

Offset lithograph

56 x 38 in.

142.2 x 96.5 cm

Gift of Ronald and Frayda Feldman

The New School Art Collection

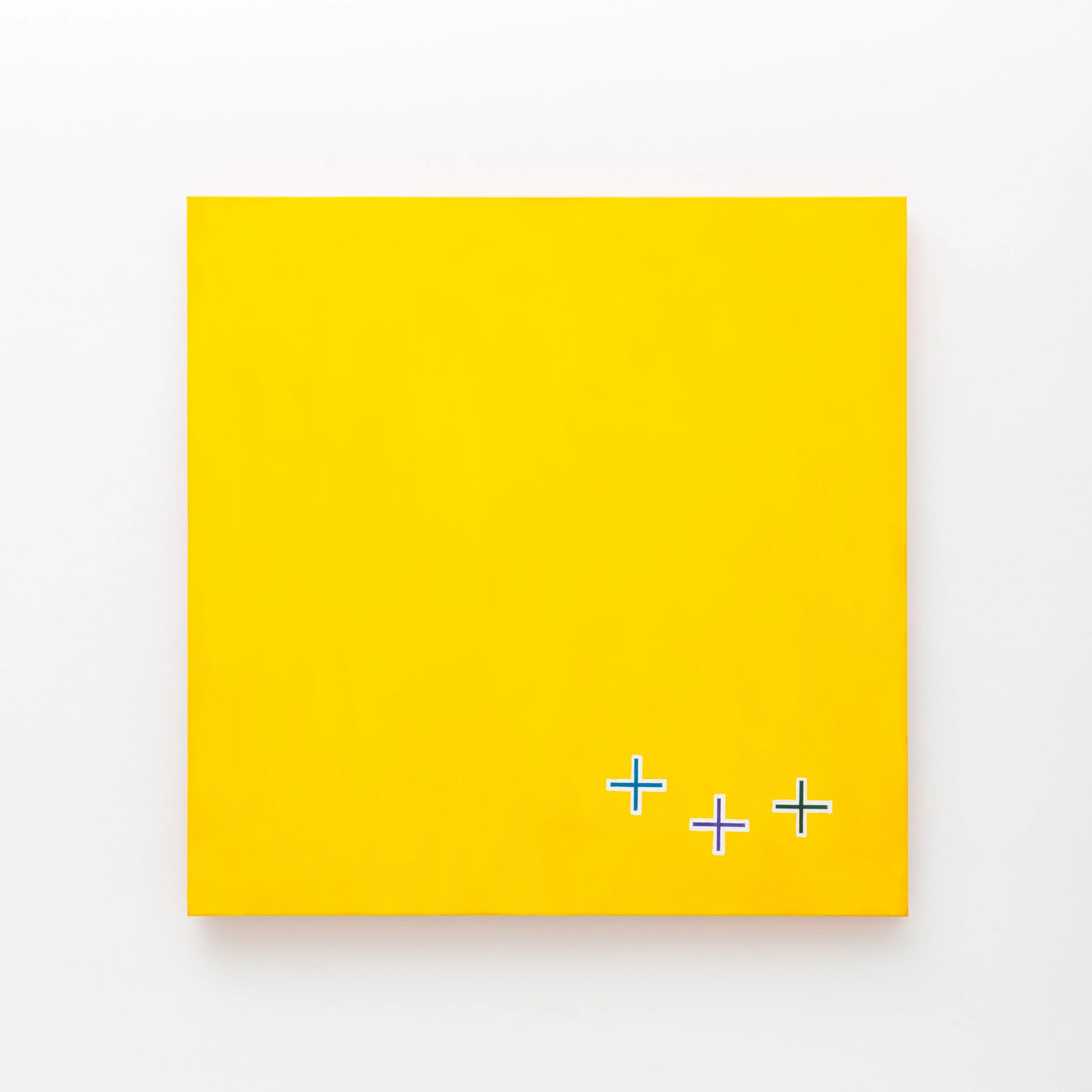

Ahchipaptunhe

Tamanend the Affable

2024

Oil on canvas

36 x 36 in.

Julianna Dail

Modern Retreat

2008–09

Nylon rope, acrylic paint, and resin

8 x 64 x 36 in.

Ian Manseau

Residue (Formation of 50 Vessels)

2025

Ceramic, glaze, donated military uniforms

28 x 24 x 6 in.

Yilong Li

Where Have All The Soldiers Gone?

2025

Inkjet on vinyl

36 x 25 in.

Combat Hippies

AMAL (teaser)

2019

Performance, film

03:57m

Caleb Brown

Tales of the City

2025

3:06m

Various Artists

Untitled tracks, various years

Louis Bury

Where Have All The Flowers Gone?, at The New School, 12/6 - 1/4

It’s fitting, if also heartbreaking, that a song about the senseless cycle of war has made sense to adapt to so many different times and places. Pete Seeger’s iconic 1955 folk song, “Where Have All the Flowers Gone?,” has not only been covered countless times by other musicians but its poignant, repetitive lyrics are themselves adapted from a traditional Cossack song, “Koloda-Duda.” The New School’s group exhibition, Where Have All The Flowers Gone?, curated by Stephanie Andrews and the university’s Center for Military-Affiliated Students, adapts ideas from Seeger’s song, as referenced in Sister Mary Corita Kent’s 1969 serigraph, Manflowers, for an art historical context. The exhibition acknowledges recurrent motifs in artistic portrayals of military bodies, while also considering how and why recent such portrayals differ from historical ones.

About two-thirds of the seventeen artworks in Where Have All The Flowers Gone? were made in the past five or so years by U.S. veterans, or their close relatives, with the balance coming from The New School Art Collection and dating back as far as the Vietnam War. This emphasis, combined with the fact that the New School works span almost every decade between the 1960s and 2000s, means that the exhibition isn’t making an argument about a narrow art historical corpus so much as using notable works from the university’s collection to help understand recent veterans' art. The conceit calls attention to how infrequently New York City art institutions center veterans’ and their families’ perspectives.

This blindspot might seem political — as if veterans’ work can’t be trusted to say or do the polite thing — but is first and foremost structural, along familiar class lines. During the half century the exhibition spans, U.S. fine art careers have grown both more professionalized and more precarious, requiring increased training (and, often, increased debt) for slim odds of livable remuneration. These conditions filter for students who can afford to take the financial risk rather than those who view college, or full- or part-time military service, as a path toward middle-class stability. What’s more, during the time when most veterans are busy training and serving, their artistic peers are progressing through the BFA, MFA, and residency pipelines. The selection pressures at each educational and professional checkpoint make it harder for veterans to achieve even modest artistic career recognition in a timely fashion.

These professional circumstances make Sister Mary Corita Kent a surprisingly kindred historical spirit for a show focused on recent veterans’ art: as a nun who left the convent at age 50 to pursue art full-time, she also had an uncommon perspective on that pursuit. The upper section of her serigraph, Manflowers, contains a photographic image of two wounded soldiers, one tending to the other. The colorful lower section contains two phrases: “MANPOWER!,” in stencilled lime green font; and “Where have all the flowers gone?,” in jaunty purple lettering. The work’s portmanteau title conflates the two phrases to suggest that the depicted soldiers’ wounded bodies have metaphorically become the delicate flowers whose disappearance Seeger’s song laments.

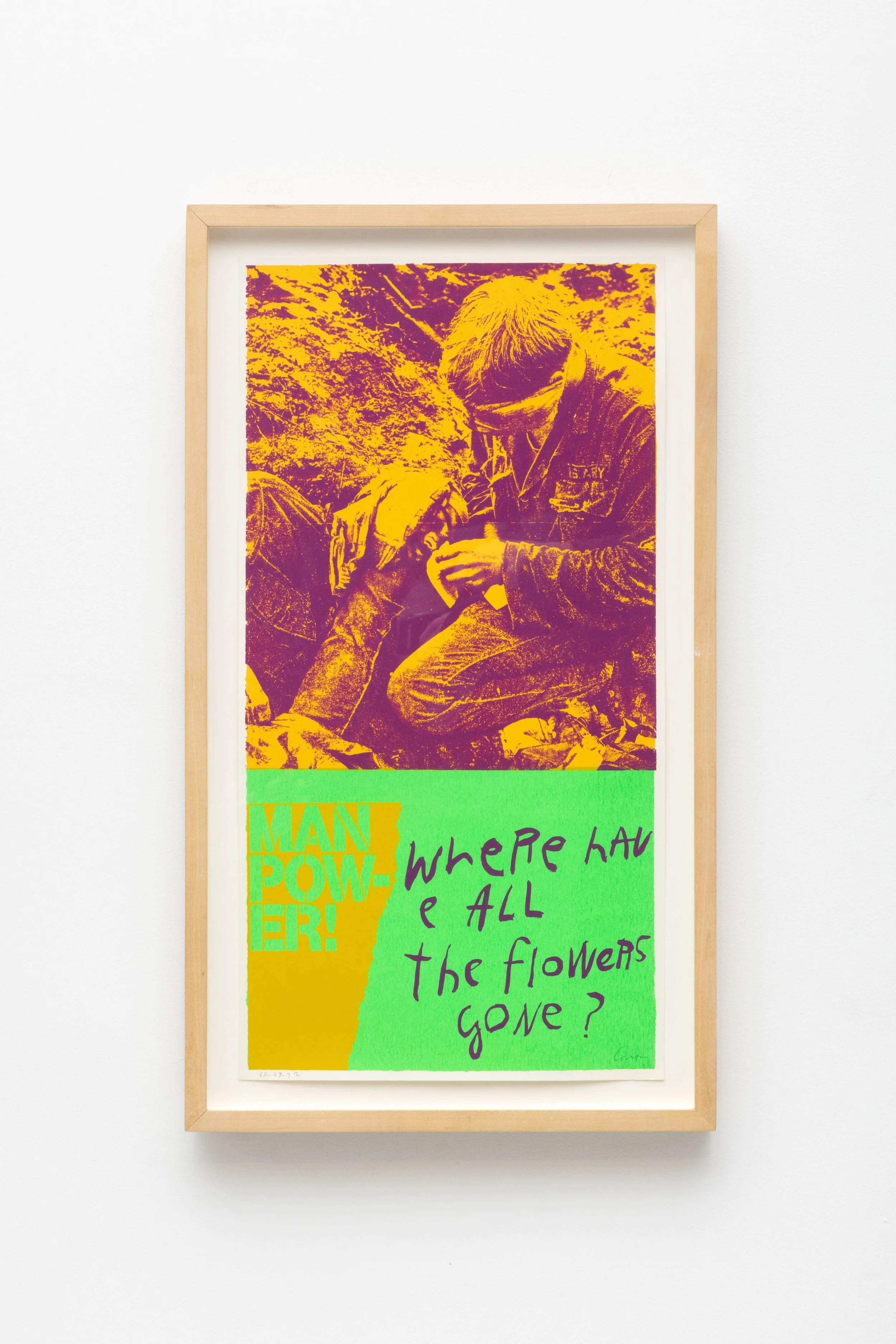

Many of the contemporary artworks in Where Have All The Flowers Gone? also center around actual or metaphorical bodies. Nicole Goodwin’s photograph triptych, “Ain't I a Woman (?/!): Kingston Legacy IV” (2021), documents a street performance she did, in which the disabled Black queer artist agonizes over a shredded American flag, her topless torso streaked red as if with blood, to protest the country’s growing anti-woke sentiment in the early 2020s. Luek Collins’ polaroid, “Self Portrait (Nude, in Front of the Gun Wall in My Father's Doomsday Bunker)” (2024), likewise places the artist’s exposed queer White body — seated back to the camera, with one butt cheek slightly lifted — in a prominent, vulnerable position. Katrina Buckles, a military spouse for over 20 years, contributes a surrealistic image of the Washington Monument mirrored at its base along the horizontal axis; the two-pronged phallic obelisk floats in the sky like a UFO (“Washington Monument,” 2025).

While these images all feature an isolated, semi-sexualized central figure, other contemporary works in the show emphasize bodily collectivity. Kevin Sparkowich’s oil painting, “Nuclear Family” (2025), portrays a crowd of pumped up Marines from a blurry photorealistic vantage that heightens the sense that the soldiers’ individual identities dissolve into that of the ecstatic group. Video documentation of Combat Hippies’ upbeat musical and theatrical performance, AMAL (2019), captures the mixed emotions of Puerto Ricans who serve in the military for a country that doesn’t grant them the same rights as U.S.-born citizens. Both artworks convey the elation of group belonging, tempered by awareness of that belonging’s potential for Romantic excess.

Other contemporary works in Where Have All The Flowers Gone? contemplate military bodies in more oblique ways. The sooty, rough-edged circle in Ian Manseau’s flocked screenprint, “Formation (Failed)” (2025), for example, looks like a haunted geometric abstraction but is actually an image of his and his partner’s unsuccessful IVF treatment, likely caused by infertility from the artist’s exposure to military base burn pits. The three small crosses in the bottom right corner of Ahchipaptunhe’s ochre color field oil painting, “Tamanend” (2024), symbolize the Lenape clans (Turtle, Turkey, Wolf) yet also recall iconography found in common military technologies such as scopes and rangefinders. Green Beret combat medic Alejandro Emilio Aguirre’s photograph of his empty quarters during his most recent deployment, “Undisclosed: Home is what you make it” (2025), together with the letters written to him by school children that he’s hung in the New School gallery window, suggests the interplay of presence and absence in soldiers’ personal lives as well as their art.

Seeger’s song laments civilizational patterns of wartime coming and going, presence and absence: the young girls who pick the flowers have “gone” for husbands, who in turn have “gone” to war as soldiers, who in turn have “gone” to graveyards, where eventually they become the flowers that the young girls pick. In establishing a comparative art historical context, Where Have All The Flowers Gone? asks what role visual art plays as such patterns unfold. The exhibition’s uncomfortable answer is that art registers how each generation tends to learn from its predecessors’ mistakes the hard way: by making similar mistakes themselves. Soldiering’s physical pains and pleasures constitute the kind of knowledge that, like knowledge of aging, no matter how strongly others try to impress it upon you, never fully sinks in until you experience it yourself.

You can glimpse archetypal themes in Joseph Beuys’ introspective protest gaze (“Joseph Beuys at the New School poster,” 1974), Enrique Chagoya’s caricatures of cultural iconography (“The Ghost of Liberty,” 2004), and other of the exhibition’s historical works. But it’s Juan Genoves’ gloomy “Escalada” (1967) that conveys a visceral recognition of militarized knowledge with particular menace. The painting’s four horizontal panels each depict, from increasingly zoomed out aerial vantages, a mass of people — each one not much more than a dark speck — running in the shadows of a plane squadron. It’s unclear whether the people are soldiers or civilians, the planes hostile or friendly, but the portentous mood is unmistakable. Living in the shadow of war is a frightening thing, whatever your exact relation to it.

The exhibition’s inclusion of Yilong Li’s aerial landscape photograph, “Where Have All The Soldiers Gone?” (2025), suggests that shadow extends onto sunny-seeming civilian life. The near-abstract image depicts a lone tree, from a direct overhead drone vantage, in the center of a field scarred with alternating matte yellow and purple vertical stripes. It’s a pleasing composition, something like a cross between an Ed Burtynsky photograph and an Agnes Martin painting, but it seems a curious fit for the exhibition, given that the photograph’s contents have no apparent connection to the military or the human body. However, similar to how the perverse beauty of Burtynsky’s landscapes highlights our species’ estrangement from its out-of-sight, out-of-mind ecological harms, Li’s solitary tree, surrounded by tidy anthropogenic scars, hints at the physical and psychological alienation from war that subtends civilian life.

That, too, is a lesson each generation mostly has to learn for itself, from both a civilian and a veteran perspective. What’s different today are the technologies — from Zoom calls with loved ones, to drone reconnaissance photography — available to mediate the cycles of military absence and presence that Seeger and others have long made art about. Drones not only enable a distinct type of remote warfare, making it feel oxymoronically “safer,” at least for some, but also facilitate surveillance in both military and civilian life, making it easier, to paraphrase an infamous Donald Rumsfeld line, for people to know what they don’t know. Within that high tech information environment, which by turns creates and collapses a sense of distance, Where Have All The Flowers Gone? affirms veterans’ good old-fashioned presences, all the vulnerabilities and joys and scars that art repeatedly limns.